|

|

|

British Colours 1747-1815,

History and Appearance (2)

Problems in

Reconstructing Historical British Colours Three ways

British colours are misrepresented Why? The "Standard

References" on British Colours |

|

So What’s the

Problem? There are three

ways in which British colours of the period 1747-1815 (an arbitrary

cut-off date based on end of the American War of 1812 and the

Napoleonic Wars in Europe) are routinely

misrepresented: 1) The central designs

are drawn far too large in proportion to the whole flag. Left: original colour, 9th Regt of Foot. Although

this flag has been reassembled from mere rags of the original, note

that embroidered wreath is only about 1/4 size of British union

in corner. Note also that white

fimbriations to central cross are much wider than depicted in

drawing on right, and nearly as wide as the corner-to-corner

cross of St Andrew. From Gherardi Davis, Regimental

Colors in the War of the Revolution, 1907.

Right: Davis's drawing of same

colour, in same book. |

|

2) The colours are drawn,

particularly the King's colours, with the white

fimbriation—the white strips that separate the red cross of St

George from the blue field of the flag, far too narrow, and often

as not, the white corner-to-corner cross of St Andrew far too wide,

both of which give the colours a very different

appearance from their actual appearance in life. These

mistakes are compounded by the fact that most colours 1772 through

the 1780’s were made with just the opposite attributes: their white

fimbriations were wider, and the St Andrew’s cross

narrower, than per regulation. 3) The central designs are

drawn so freely as to give the impression that there was little

regularity among the regiments. In fact there were standardized

designs, almost certainly associated with individual makers, which

account for by far the largest number of colours that survive from

the period, suggesting that those colours which have not survived,

would nevertheless have been very much like those that have. |

|

Why? Simply put, the "standard"

references are wrong, or at least misleading. Samuel Milne Milne’s

Standards and Colours of the Army has been the

standard reference on British colours since its publication in

1893. Milne’s desire to adequately portray the salient points of

art and design in British colours, however, led him to draw

the designs on the flags much larger than they would appear in

life. This would be akin to doing uniform plates with buttons,

lace, or belt plates at twice their natural size; it might

better show the details of these uniform parts, but it could also

lead to paintings, posters, second-generation book illustrations,

movies, and re-enactors sporting uniforms with three-inch buttons

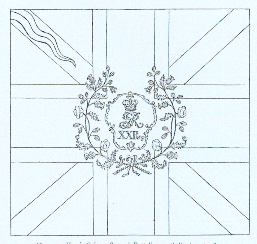

and lace, and belt plates the size of typing paper. Left: Milne's Plate of the King's colour of the 2d

Battalion of the 1st, or Royal Regiment, c. 1747. Milne

purposely drew the central device larger than life.

Right: Same colour made according to Napier's scale

drawing. Flags that have survived follow the standard pattern

to a fairly high degree. |

|

While Milne clearly stated his

purpose in the introduction to his book, apparently very few have

bothered to read it. British colours have been drawn ever

since with their central motifs far too large in relation to other

parts of the overall design. In book after book, the central Union

Wreath is shown spilling far out over the white fimbriation of the

central cross on the King’s colour, or filling virtually the entire

field of regimentals. Milne’s drawings might also be faulted for

ignoring accurate proportions between the crosses and the white

fimbriation on the colors, another mistake common to most later

depictions. Right: Milne's drawing of King's colour, 2d

Battalion, 20th Foot, 1800. The gold flame, or "pile wavy" descending from

the upper staff corner indicated the Second Battalion of any

regiment. |

|

The very best of the old works is

Andrew Ross Old Scottish Regimental Colours, published in

1885. The plates are uniformly excellent and appear to

have been made from photographs. Unfortunately it is

not well known, and where some of the flags in it were

later re-drawn in Milne's Standards and Colours, it

has been Milne's out-of -proportion pictures that have obviously

been relied on by later illustrators. Regimental

Colors in the War of the Revolution, published in 1907 by American historian Gherardi Davis,

gives information on British colours, illustrated with

photographs and drawings of three that were actually carried in

America. But describing specifics of pattern or design among the

colours Davis dismisses as "probably… impossible, and in any

event not especially interesting." Davis also left

several fine water-colors that have been widely published in

The American Heritage histories of the Revolution. Overall,

Davis shows too few British colours to draw generalizations, and

perhaps following Milne, some of his drawings show the component

parts of the colours out of proportion. Edward

Richardson’s Standards and Colors of the American

Revolution, 1982, while giving much useful information on

American and French colors, is simply wrong in almost every respect

when it comes to the British. Dino Lemonofides, British Infantry

Colours, 1972, has acccurate text, but Milne-style

out-of-proportion drawings. The very handsome new

British Colours and Standards 1747-1881, by Ian Sumner and

Richard Hook, in the "Osprey Elite" series, includes most of the

same mistakes as other books on the topic. |

|

|